All children deserve a quality education. Together, we can help them reach their dreams.

Learn more about Teach for Life, the educational branch of Trees for Life.

Ixtahuacan, Guatemala

Natividad struggles daily to provide food and shelter for her children Maria Isabel and Chepe. In her work with Trees for Life, she is also planting the seeds of hope for future generations.

It all started with a mystery. I was in Ixtahuacan, Guatemala working with villagers on a Trees for Life project. Every day during my first week there, the mystery would occur.

Each morning I hiked to villages in the surrounding hills to work with local people. Then in the evening I would climb the dirt road to my own adobe hut at the tree nursery. It seemed like every time I returned home I was greeted by a gift left on my table. Sometimes it was a bunch of bananas, other times sweet drinks or bread. But there was no sign of how the gifts had gotten there.

When asked some of my Guatemalan neighbors, they said a local woman had left the gifts for people working on the Trees for Life project.

I often wondered about this woman. Who was she? And where had she come from? But she remained a mystery to me throughout that first week.

Lending a hand to help protect their fragile environment,farmers in Ixtahuacan, Guatemala build a cover for their community's fruit tree nursery.

One day as I worked at the village tree nursery, I looked up and saw a new face: a young woman dressed in traditional red hand-woven clothing, her long black hair hung in the customary braid. She approached the nursery bed where we were working. Her native Mayan features radiated dignity.

One of my co-workers quietly told me this was the woman who had brought the gifts. When I asked her name, she answered, "Natividad."

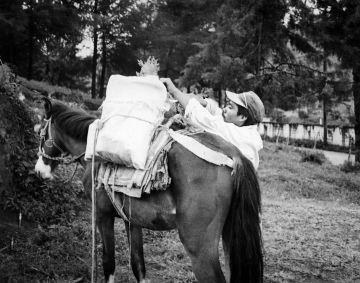

Showing a mother's care for her papaya trees, Natividad prepares to teach her neighbors in the highlands of Guatemala how they can grow their own fruit.

Natividad must have understood the look of curiosity on my face, for she sat down with us and began telling her story in her native language. I listened with rapt attention.

She told of the recent history of her people and the struggle she had been through as a refugee. Natividad is one of hundreds of thousands of Guatemalans who have suffered from 35 years of military repression and civil war.

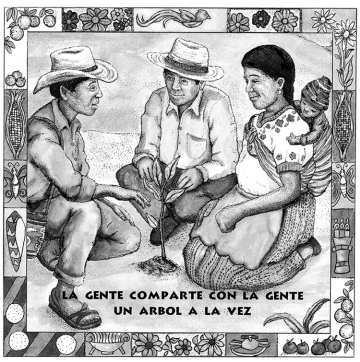

This Trees for Life booklet entitled "People Sharing with People One Tree at a Time" was designed with the help of villagers in Guatemala.

A shadow seemed to pass over her face. Carefully and painfully she told how, one night as she and her family slept in their small hut, men from the military stormed into her home and took her husband. She never saw him again. "From that moment I was a widow. My son was very young, and I would soon have a daughter, also," she said.

Like thousands of Guatemalan peasant farmers, Natividad and her young son fled to Mexico. "We never felt safe," she said. "We hid in the forests and the mountains. We had no home."

Natividad and her son suffered homelessness, sickness and hunger to reach the Mexican border by foot. For them, the war was a time raging with fear, violence and death.

When Natividad finished her story, we sat in silence. I studied her face. It showed suffering, but also something more-a great strength.

The shadow seemed to lift from her face. "Now we have returned here to our home," she said slowly, "the home of our ancestors. Now we can live again."

I had worked with many refugees of the war, so I knew that returning home was also very difficult, especially for a widow and her children.

Then I remembered the mysterious gifts left on my table. How could this woman afford to be so generous? "You have been bringing those gifts?" I asked her.

Natividad smiled. "I heard of the work you are doing here at the tree nursery, and I am grateful," she said. She explained that as she learned about the work her community is doing with Trees for Life, she was very inspired by it. Then a broad grin broke out on her face. "I am a volunteer also," she stated proudly.

"My family has a small one-room store, and I work there so I can feed my children. When I am not tending the store, I work with the 'One Teaches Two' project."

"You do?" I asked in surprise. I had worked with volunteers in Guatemala and the U.S. to create a booklet for that project. But since many villagers are illiterate, I often wondered how effective it would be. Now Natividad was using that booklet in her efforts.

Before she left, she invited me to visit her home sometime soon. I said I would look forward to visiting her.

With its many colorful illustrations, one does not have to read to use the booklet in teaching two friends to plant fruit trees.

A few days later I made my way to Natividad's home, anxious to learn more about her and her work. When I stopped at her small hut, she went into a back room and returned with several sheets of paper in her hand. With the papers was a copy of the "One Teaches Two" booklet.

Natividad opened the booklet and pointed to some of the colorful drawings. "These pictures show how each person can share their knowledge and experience with two other people," she said.

By giving care and attention to fruit tree seedlings, one person's efforts become part of a movement that touches the lives of countless people.

She described how she walks from village to village through the rugged mountains to demonstrate this process with her neighbors. "I teach them how to plant and care for papaya fruit trees," she said. "Then each one who learns becomes a teacher. They pass on what they have learned to two other people. One teaches two."

Then she showed me the papers she had brought out, on which she had carefully written the names of all the villagers who had learned to plant papaya trees. "At first I had many failures," she said with a chuckle. "But I kept working."

This is one of the many illustrations from a Trees for Life booklet used by villagers in Guatemala. "It shows how each person can share their knowledge and experience with two other people. One teaches two."

"How many people have you taught?" I asked.

"I got ten people started," she said. "Then they began teaching others. After a few weeks, the number of people who had planted fruit trees and taught others was . . . " She consulted her papers. "One hundred eighty-two."

I looked at Natividad in awe. She had started a powerful chain reaction that would benefit countless numbers of her people. She had certainly answered my doubts about the impact of the booklet.

To me, Natividad still represents a mystery-but it is a different kind of mystery. Considering all that she has been through, she would seem to be a victim. So much had been taken from her by hatred and violence. But even with so little to call her own, she is demonstrating the power of people working together for hope. She has shown me that miraculous power in each person-truly a wondrous and divine mystery.

Inspired by their knowledge, local volunteers devote precious time and energy to sharing tree seedlings and training with other villages.